John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood: Influencing the Influencers – Was Disney Sleeping? (Book Excerpt and Analysis)

John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood looks at the entire 100 year history of the journey from the release of Edgar Rice Burroughs A Princess of Mars in February 1912, to the release of Disney’s John Carter in March 2012, including all the failed efforts to get a film made, as well as all the creative and production decisions made by Andrew Stanton and his team. But one aspect in particular that caught my attention as I was researching the story was the role of the “influencer media” — and how Disney mystifyingly ignored these key voices who are crucial both as a means of generating positive “buzz”, and as a means of obtaining feedback at the earliest stages of a campaign — feedback that if properly analyzed, can help enable course corrections that can be critical for the success of a campaign.

Who are the influencer media? In the case of movies they are a number of publications and websites who track movies from the time they are first announced until well after they are released. They are the sites who were speculating about John Carter of Mars as far back as 2007 — would it be animation, live action, or a combination of both? They were the ones who were on top of Disney’s decision in January 2010 to move the release date forward from June 8, 2012, to March 8, 2012; they were there when Disney changed the title from John Carter of Mars to just John Carter in May 2011; and they were there reacting to teaser poster in June 2011, the teaser trailer in July 2011, and they were there every step of the way once the final push begin on November 30, 2011. They are sites like Ain’t It Cool News, Slashfilm, Collider, ComingSoon.net, JoBlo.com, iO9, ScreenRant, HitFix, Movies.com, BleedingCool.com, Badass Digest, Cinemablend, ComicBookMovie.com, Geek Tyrant, and quite a few more — and collectively they and their readers (who comment vociferously and who themselves chatter on Twitter and Facebook and their own blogs) collectively generate the “early buzz” that goes a long way toward determining whether a film goes into the marketplace with wind in its sails, as studios hope will be the case — or facing major headwinds, as was the case with John Carter.

In the case of John Carter one of the very interesting things that I discovered, for example, is that the negativity that would eventually engulf the film as it neared its release date was not something that was there from the beginning. In fact, there was virtually no negativity at all in the media about the project until as late as January 2011. It was then, on January 19, 2011, that Disney announced that it was moving the release date forward from June 8, 2012, to March 8, 2012. This announcement created the first ripples of negativity — not so much in the articles that were written, but in the comments, where people started questioning Disney’s commitment to the film, and confidence in it. There was a whiff of “something must be not right” for Disney to move the film out of a primetime summer slot where every day is a weekend and where the combined available monthly box office “pie” is typically $1.5B, to a March release date where the combined monthly box office “pie” is typically $750M. This is where the negativity began.

But the real negativity kicked in later, in May 2011, when Disney announced the name change from John Carter of Mars to John Carter — that was when the chorus of “what’s going on here?” really started. Some examples: Adam Chitwood at Collider.com called it “disappointing,” Eric Eisenberg at CinemaBlend called it “quite confounding,”and GeekTyrant’s Joey Paur called it “stupid” and a “brain fart,” adding: “That’s a boring title and it’s just distanced itself even further from the Edgar Rice Burroughs classic novels from which the film was adapted. So how is that helping the movie? It’s not.” Slashfilm’s Germain Lussier wrote:

Double Academy Award-winning director of Finding Nemo and WALL-E, Andrew Stanton, is currently working on his first foray into live action, an adaptation of the classic sci-fi fantasy novel John Carter of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs. For some reason, though, Disney has now changed the title from that to “Gary Carter,” the Hall Of Fame catcher for the 1986 New York Mets. No, I’m sorry. I meant John Carter. That’s the new official title. For real.

The wave of negativity was such that some degree of damage control from Disney might have been expected — but none materialized. The campaign just stumbled forward toward the June 2011 release of the teaser poster, and the July 2011 release of the teaser trailer, with a buildup of negativity and skepticism creating an atmosphere in which it was increasingly unlikely that the poster and trailer would be well-received. And of course when they came out — the reaction was not what Disney or any studio would be looking for. Did the skepticism engendered by the poorly handled announcement of the name change play a role in conditioning many influencers to react negatively to a campaign that seemed already to be floundering? It’s not possible to definitively state that there was cause and effect — but if you drill down and follow the conversation from May through July 2011 cross all the influencer sites on the internet, it is difficult to not come away with the impression that skepticism that coalesced after the name change announcement contributed to the negative response to the poster and trailer.

But the real kicker that doomed John Carter was not the skeptical reaction after the name change — it was the “are they crazy?” reaction that ensued after Disney let word out that the budget of John Carter was $250M. Until August 2011 — 8 months prior to release — the only Disney mention of the budget was $150M, a figure that was floated in June 2009 when Disney announced the casting of Taylor Kitsch. After that, Disney didn’t mention the budget ant it wasn’t an issue in the media until August 2011 when Rich Ross pulled the plug on The Lone Ranger, and in the announcement as covered in Deadline Hollywood came the first ever revelation that John Carter had cost a whopping $250M:

This had to be an incredibly tough call for Disney’s Rich Ross and Sean Bailey, but they have several huge live-action bets on the table already. Budget busters include John Carter, the Andrew Stanton- directed adaptation of John Carter of Mars with Friday Night Lights‘ Taylor Kitsch in the lead role, which has a budget that has ballooned to around $250 million . . .

The influencers immediately picked up on this and questioned the wisdom of spending that much on a movie that did not have a large, current, built-in fan base–and the release it in March. It was from that moment — and only from that moment — that the budget of John Carter became an issue that would dog it throughout the remainder of the promotional campaign.

In building a detailed timeline of all of the publicity about the film, it became clear that there were distinct “pivot points” in the campaign when a particular event or announcement had a clear and demonstrable effect on the influencers’ tone of coverage of the film . . . providing Disney with important feedback that seemed to be ignored. It was as if Disney was operating on a philosophy that all these “little chattering voices” as well as the “little chattering voices” on Facebook and Twitter (where Disney’s effort was pitifully puny in direct comparison to the main competition Hunger Games and stablemate Avenger — details in the book) just didn’t matter, and that the campaign would be able to define itself and succeed without reference to this buzz, which was growing more and more negative by the month.

Aside from not taking the feedback from the influencers and doing something with it — the other thing that jumped out of the research was the demonstrable lack of effort to pump out “publicity fodder” for John Carter at a pace or volume that was comparable to other films of its budget, genre, and stature. For example, I did a side by side comparison of John Carter and The Hunger Games (its main competition for the March 2012 buzz) to measure the amount and frequency of article fodder put out there by the publicity team — and it was “no contest”, with Hunger Games far outstripping John Carter in every measurable category of publicity activity. This was also true of the Hunger Games social media effort on Twitter and Facebook, which was far more sophisticated and effective than Disney’s efforts on behalf of John Carter. (Details of the two social media campaigns are analyzed in the book.)

But then, Disney is Disney and sometimes they do things differently, so I also measured the John Carter digital marketing and social media output in comparison to its stablemate, The Avengers, who was 10 weeks behind John Carter in the Disney pipeline. What I found was that the gap between John Carter and The Avengers was even greater than the gap between John Carter and the Hunger Games — meaning that the weakness of the John Carter effort was not just a “Disney thing” — because Disney showed it was completely capable of a robust effort with its handling of The Avengers.

To understand the order of magnitude of the failure to promote John Carter on an equal footing with either The Hunger Games or The Avengers, consider this: During one 12 week period when The Avengers, The Hunger Games, and John Carter were all marching toward their release date, the number of publicity placements generated for John Carter and monitored by the Internet Movie Data Base’s publicity monitoring system showed 1100++ publicity placements for The Hunger Games, 1400++ placements for The Avengers, and 45 placements for John Carter. That’s right — 1100, 1400, and 45 for John Carter.

Another monitored period showed 276 placements for Avengers, 150 for The Hunger Games, and 5 for John Carter.

These are hard numbers, derived from an independent source — IMDB Pro Publicity Monitoring — and fully footnoted in the book.

Is there a conclusion to be drawn from the evidence that is available? Frankly, I’ve tried to be very careful about that. What I’ve done is to dig to find the evidence, and to present it in a rational, verifiable manner. The verifiable facts speak pretty loudly. I do draw some conclusions in the book, but in the interest of “spoiler” they won’t appear here — not just yet, anyway.

Well . . . at the outset I meant to write just a brief intro to the following excerpt from the book. It’s turned out to be a lot more than a brief intro — but here, as promised, is the excerpt from John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood:

Influencing the Influencers – Was Disney Sleeping?

Excerpt from John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood

With a major theatrical release motion picture, some degree of marketing is present from the moment the picture is approved to go into production. Typically this early activity takes the form of press releases announcing the green-lighting of the project; announcements of the signing of director and stars, the beginning of principal photography, and other milestones. This is also the period in which decisions are made regarding what level of cross-promotional tie-ins, and which merchandising deals, and licensing arrangements will be pursued. If these are to be pursued, the effort to identify partners and develop deals — which can often require substantial lead time–is launched.

Increasingly, studios also use this period to get an early head start on building ‘buzz’ for the film through social media platforms like Twitter, and Facebook, and through outreach and reputation/relationship management with key “influencers” who track movies and write about them from the time they are announced until well after they are released. Effective management of the pool of influencers and the key social media platforms is significant to a studio both as a means of generating buzz — and equally important, as a way of monitoring reactions to the marketing materials and messages that are released. Notes Pete Blackshaw, Executive VP of the Nielsen Online digital strategic services:

The name of the game for the studios is to take full advantage of all early signals. The downside for them is a movie can be damaged really quickly — the flow of information on these platforms, and degree to which influencers are tapping into those signals is quite profound.

Thus there are two functions for the influencer media and social media platforms — one, to “spread the word” and generate buzz, and two, to provide a feedback loop that allows the studio to monitor what Blackshaw calls “all early signals” and right the ship when it needs to be righted, early in the game when the audience is small and mistakes, if corrected, can be minimized.

For John Carter of Mars, mechanisms of influence that were available and relevant at the early stage of the John Carter campaign were:

1) Traditional Trade Publications: Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, plus Hollywood pulse-o-meter Deadline Hollywood. These are the “traditional” source of influence from the mainstream trade media, and remain important. Not widely read by the public, they are nevertheless monitored closely by key blogs and entertainment outlets (“2” below) who replay information derived from the trades.

2) Key Entertainment Bloggers and Websites: About 40 key blogs and entertainment sites collectively reach as much as 80% of the audience for early reporting on movies-in-progress. Among the most active influencer media outlets with the largest audiences are Movies.com, Hit Fix, MovieWeb, MTV Movies Blog, Slashfilm, i09, Ain’t It Cool News, (whose founder Harry Knowles had been attached as a producer on Paramount’s John Carter of Mars), ComingSoon.net, Filmsite.com, Collider.com, Badass Digest, Joblo.com, Empire Online, Total Film, ScreenRant, Hollywood.com, MovieWeb, Movieline, Indiewire/The Playlist, Dark Horizons,ToplessRobot, Fused Film,Den of Geek,Film School Rejects, HeyUGuys.com,FirstShowing.net, Cinema Spy, Digital Spy, The Geek Files, GeekTyrant, Comic Book Movie, Reelz Channel, Cinema Blend, WhatCulture.com, and as many as a dozen others.

3) Key Social Media Platforms Twitter and Facebook: These two social media platforms are of strategic importance and building a strong list of followers on each is important, keeping in mind that the early followers on these platforms are most likely to themselves be “mini- influencers” likely to tweet and comment about a film they are excited about. Many have their own personal blogs and/or have extensive networks of their own on Facebook and Twitter and thus one follower on Twitter or Facebook equals many hundreds or even thousands of “followers of the follower”, who in turn have their own networks. Disney had available both the official John Carter Twitter and Facebook presence; and the official Walt Disney Pictures Twitter and Facebook presence.

4) Disney Bloggers: In addition to the other outlets that apply to all movies, Disney maintains a “Disney Blogger” network which has as many as 500 blogs devoted to all things Disney. With names like Disney For Life, Mouse Dreaming, Babes in Disneyland, The Disney Dork Blog, Disney Fan Ramblings, Stitch Kingdom, and Adventures By Daddy, Everything Walt Disney World, the Disney bloggers are positioned to exert influence on Disney enthusiasts, but are generally not “in the same league” as the top entertainment blogsites in terms of audience reach and relevance to the potential John Carter audience.

The task before Disney at this early stage was to manage their Twitter and Facebook profiles effectively, and to maintain a flow of good information and materials to this manageable “ecosystem” of “influencer” bloggers and journalists and “mini-influencers” who are the early adopters on Facebook and Twitter.

Breaking Down the Influencer Media

At the top of the Influencer ecosystem are corporate owned megasites like the Internet Movie Data Base (estimated 80M unique monthly visitors), Yahoo Movies (estimated 27M unique monthly visitors), Rotten Tomatoes (estimated 7M unique monthly visitors), and Fandango (estimated 6.8M unique monthly visitors).99

However, when it comes to tracking movies a year or more in advance of their release, the influencers tend to be a more independent and colorful group, none moreso than Harry Knowles of Ain’t It Cool News. In 1997, the second year that AICN was in existence, Bernard Weinraub wrote in the New York Times:

Harry Jay Knowles is Hollywood’s worst nightmare. In an industry whose executives, agents and producers ferociously seek total control — over information, over the media, over one another — this 25-year-old college dropout and confirmed film geek is driving them crazy. His power comes from the bits and bytes of information and gossip spread over his rapidly growing Web site (http://www.aint-it-cool-news.com), which is averaging two million hits a month. He works out of his father’s ramshackle home in Austin, Tex., but his impact in Hollywood is extraordinary–and instantaneous.

Of the influencers who focus on upcoming movies, ComingSoon.net is one of the largest, with an estimated 1.6M unique monthly visitors, while MovieWeb, Movies.com, and Hollywood.com each have an estimated 500,000 unique monthly visitors.101 Slashfilm,started by Peter Sciretta in 2005, has an estimated 510,000 unique monthly visitors counts 74,000 Facebook fans, carries a Google Page Rank of 7, and has won more than a dozen major awards. Collider.com, with 32,000 Facebook Fans and a Google Page Rank of 7, is self-described by editor-in-chief Steve ‘Frosty’ Weintraub, as “an uncalled for, online barrage of breaking news, incisive commentary and irreverent attitude that will do for the internet what Art Modell did for the Cleveland Browns; i.e.move it to Baltimore.” Sci-fi site iO9 under editor-in-chief Annalee Newitz boasts 161,000 Facebook fans and a Google Rank of 7, and defines its beat as “science, science fiction, and the future.” UK based Total Film, with 125,000 Facebook fans, touts itself as “The Modern Guide to Movies” while ScreenRant, which was started in 2003 by Vic Holtreman “as a place to rant about some of the dumber stuff related to the movie industry,” sports 140,000 Facebook Fans and a 7 GoogleRanking. Other top influencers include Hit Fix (54,000 Facebook Fans and a 6 ranking), and Digital Spy ( 47,000 Facebook Fans and a 6 ranking). (Note: All Facebook Fan references refer to the number of “Likes” on the publication’s Facebook page as of 11 Sep 2012. Google Page Rank index refers to the Google Page Rank as accessed on 11 Sep 2012 at http://www.prchecker.info/

These, plus a few dozen others, represent a critical mechanism through which a studio can lay a buzz foundation and, equally importantly, keep an ear to the ground for feedback on what is working, and what is not working, as they roll out a film.

Disney: The View From the Outside Looking In

For an outsider following the JCOM story, this “Preliminaries” phase was unusually long and characterized by sporadic press releases that began in January 2007 with the announcement that Disney was pursuing the Edgar Rice Burroughs Property “A PrincessofMars.” There were then announcements that Andrew Stanton had been signed to direct the film, and that Michael Chabon had been hired to do a rewrite. Then came the announcement, on June 15, 2009 that Taylor Kitsch and Lynn Collins had been cast as the leads in the film. Some of the articles announcing the cast signing include reference to a budget of $150M:

Canadian film actor Taylor “Friday Night Lights” Kitsch has been cast as the lead in Disney’s upcoming adaptation of author Edgar Rice Burroughs’ John Carter Of Mars, to be directed by Andrew “Wall-e” Stanton in 2010. Stanton confirmed that the $150 million budgeted sci fi production, will be live-action. “There are so many creatures and characters that half of it’s going to be CG,” he said. “but it will feel real. The whole thing will feel very, very believable.”

Later in the summer of 2009 there were more cast announcements.106 There was silence in September (the month that studio chief Dick Cook was fired) and in October (the month that Rich Ross was hired as the incoming studio chief). In November, evidence that Ross was reviewing all projects came in the form of a press release that Disney had halted production on Captain Nemo: 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea — a press release that included assurances that this did not mean that Disney was abandoning major event films under Ross, stressing “big event films like 20,000 Leagues, John Carter of Mars, and Tron are still a priority.”

In the social media arena, on November 28, 2009, Disney created a Facebook page for John Carter of Mars, although no entries were posted until January 2010. Then as JCOM began principal photography in January 2010, more releases came, announcing additional cast acquisitions and eventually, on January 16, 2010, came the official announcement that principal photography had begun in London.

OnFacebook, January2010 saw Disney make its first socialmedia efforts, posting four articles with links and posting the official synopsis for the first time:

From Academy Award®-winning filmmaker Andrew Stanton (Finding Nemo, WALL-E), John Carter of Mars brings this captivating hero to the big screen in a stunning adventure epic set on the wounded planet of Mars, a world inhabited by warrior tribes and exotic desert beings. Based on the first of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “Barsoom Series,” the film chronicles the journey of Civil-War veteran John Carter (Taylor Kitsch), who finds himself battling a new and mysterious war amidst a host of strange Martian inhabitants, including Tars Tarkas (Willem Dafoe) and Dejah Thoris (Lynn Collins). [Footnote: Interestingly, this synopsis was changed after the arrival of MT Carney to: “From Academy Award®–winning filmmaker Andrew Stanton comes “John Carter”—a sweeping action-adventure set on the mysterious and exotic planet of Barsoom (Mars). “John Carter” is based on a classic novel by Edgar Rice Burroughs, whose highly imaginative adventures served as inspiration for many filmmakers, both past and present. The film tells the story of war-weary, former military captain John Carter (Taylor Kitsch), who is inexplicably transported to Mars where he becomes reluctantly embroiled in a conflict of epic proportions amongst the inhabitants of the planet, including Tars Tarkas (Willem Dafoe) and the captivating Princess Dejah Thoris (Lynn Collins). In a world on the brink of collapse, Carter rediscovers his humanity when he realizes that the survival of Barsoom and its people rests in his hands. The screenplay was written by Andrew Stanton, Mark Andrews and Michael Chabon.]

Then, from February 2010 onward, with the film in Principal Photography, Disney publicity and the still leaderless marketing department went silent. Aside from a brief announcement on March 12, 2010, that Michael Giacchino would score JCOM, no visible publicity or marketing efforts were logged by IMDB Pro publicity monitoring. (The IMDB Pro Publicity Monitoring of John Carter is also available as a PDF Download here.) The Facebook page was not updated. (Note: Note: Facebook’s “Timeline” function chronicles the date the page was created, and includes each post by the page owner throughout the history of the page.) The Twitter account did not exist and would not be created until June 15, 2011; there were no announcements, including no official announcement of the completion of principal photography in July — a milestone that traditionally receives an announcement in the media.

This period of “media silence” coincided with MT Carney taking over as President of Marketing in April 2010, as JCOM was in its 52nd day of a 100 day shooting schedule. The silence continued until finally on August 15, 2010, a few weeks after the completion of principal photography, came the first mention of JCOM during Carney’s tenure — an announcement that John Carter of Mars would be released on June 8, 2012. [Footnote: The IMDB Pro Data Table publicity log for John Carter note 22 mentions of John Carter from February 2010 through August 8 2010. Other than the announcement of Giacchino being brought on board to score, all mentions appear to be unrelated to any Disney marketing efforts; for example Bryan Cranston mentioned John Carter during an interview about his appearance in Red Tails; John Carter was mentioned by Universal in its announcements that Taylor Kitsch had been cast for that movie, etc.]

Again, “media silence” ensued after the release date announcement — a silence which continued until the end of the year. Thus in all of 2010 the total output from Disney consisted of four Facebook updates in January 2010 followed by silence on Facebook; plus(as monitored by Internet Movie Data Base) the announcement of Giacchino’s signing in April 2010, and the August announcement of the release date being June 8, 2012.

In reviewing the publicity and marketing output of Disney during 2010, the obvious inference to draw is that attention to JCOM was sporadic at best, with long periods of silence and no sign of any major engagement by Disney marketing. Such an inference would be consistent with the notion that JCOM suffered from Dick Cook’s departure; the firing of the entire Cook executive team, and the instability that followed and continued until at least the hiring of MT Carney in April 2010.

In sum, based purely on the public record of the output of the campaign from inception in 2007 through the end of 2010, it is possible only to conclude that Disney did nothing special to draw attention to the film, and limited itself to the basic output of a very few media releases, with no other visible marketing efforts taking place.

==========================

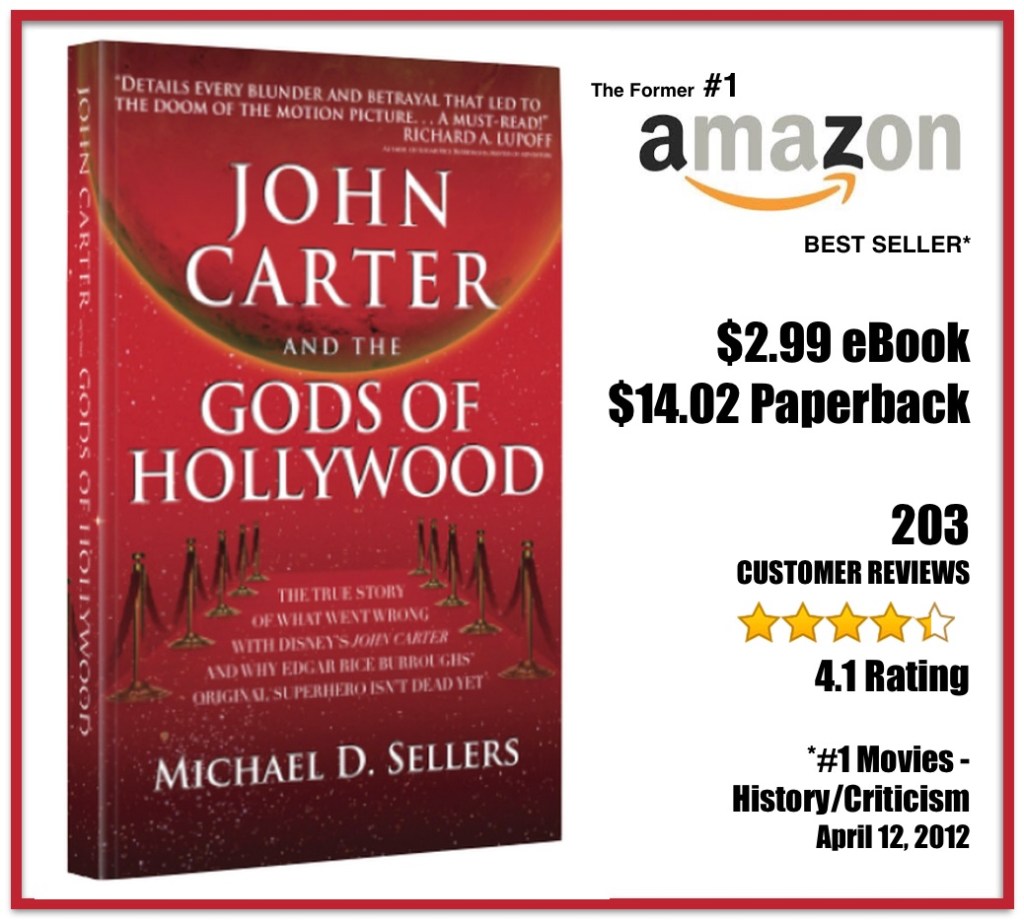

And here’s the plug for the whole book!!!!

“A fair, factual, and enlightening assessment of what went wrong . . . the best corporate history I’ve read since Disney War.” Daniel Butcher, Between Disney.

“A winning book . . . . I have no reservations in recommending John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood. Even if you only remotely hold an interest in the film or the moviemaking method, do yourself a favor and purchase this book. I cannot remember an instance when I read 350 pages of anything in 24 hours, but my level of captivation in how methodically and interestingly the content was presented should substantiate why John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood is a must-read. Grade A.” Brett Nachman, Geeks of Doom.

–

“A must read for every fan of Edgar Rice Burroughs and John Carter and every film buff intrigued by the ‘inside baseball’ aspects of modern Hollywood.” Richard A. Lupoff, Author of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Master of Adventure

“Extensively researched . . . fascinating . . . an engrossing experience, kind of like watching the Titanic headed for the fateful iceberg. Josh Whalen, AmazingStoriesMag.com

6 comments

The is only semi-shamless pimping of my site. Really. If you want an idea of what was going on in the trenches of reporting/bloggery/fandom at the time, go read my report which is in response to my reading Michael’s book. Mike and I ( of the now closed johncartermovie.com ) had received things like set invites at the same time as multiple ” hi, I’m Shirley, I’ll now be your media contact.. ” That must have happened three times. I’d say staffing was an issue. I think they worked on John Carter during their lunch breaks.

http://barsoomia.wordpress.com/2012/12/28/reading-john-carter-and-the-gods-of-hollywood-or-lions-and-igers-and-bears-oh-my/

Were other films around that time period produced in-house by Disney better served than John Carter? I’m thinking Tangled Ever After, Brave or Frankenwinnie for example. Or were they also delegated to outside consultants?

For me there are two threads to follow — effort, and judgment.

A lot of the discussion about the marketing campaign has focused on judgment, and this isn’t surprising. But anything that is a “judgment call” is just that . . . a judgment call and while it’s easy to Monday morning quarterback the choices, the facts seem to be that some professional marketers got in a room and thought pretty hard about the movie and came up with what we saw. It seems like some strange choices . . . . but it’s pretty easy to discern that there was some thought going into it, and a strategy — just the wrong one.

But effort is another thing. How does anyone explain the lack of effort? Let me try.

First, unlike the films of Bruckheimer or Spielberg, John Carter did not have it’s own marketing consultant and team. MT Carney decided to handle it “in house”, which means it went into a pool of second echelon Disney films that included, for example, the $40M “The Muppets”. The Muppets were released on November 23, and John Carter’s final push kicked off on November 28. And yes . . . most of the Muppet team moved to John Carter. Unfortunately, it was during the final push for The Muppets that John Carter went inexplicably silent — this was the period when Avengers had 1400 articles placed, Hunger Games had 1100, and John Carter had 45.

So yes, in some stupid, hard to defend way — simple staffing issues were part of it.

But why was that allowed to happen?

One, because it wasn’t a priority. Iger had decided to “give it the promotion it deserved” (his words, in an interview with Carol Massar) and that was just a basic, standard movie (not tentpole) push and that meant letting it be moribund until Nov 28.

Two, this was also the period when MT Carney was basically cleaning out her desk. She knew she was done.

Three, John Carter didn’t have a Spielberg/Bruckheimer/Feige Papa bear producer looking out for it and keeping Disney marketing on its game. Jim Morris was the most senior producer but he’s really just a technical kind of producer (no offense) . . . . he comes from ILM and is a CGI guy, not a broad gauge power player producer. So JC was unprotected in comparison to the other.

so there wer explanations, albeit lame ones.

Can you imagine — $100M advertising spend and yet the simple matter of effort comes a cropper because they want to do it in house and not spend for an outside team even though they didn’t have the resources in house to give it he push that was required.

It seems to have been an all-of-the-above situation, with the shortfalls in the marketing not really being attributable to any one particular cause. Was the lack of focus on influencer media because Disney didn’t commit enough resources to staff that kind of effort? Were those in charge unaware of how to take advantage of the influencer system? Or perhaps the marketing team became paralyzed while trying to shape the message and just couldn’t come up with much to put out? There was a tweet from someone on the marketing team from early or mid 2011, saying “John Carter is proving to be a tough nut to crack”, so, they may have been having a difficult time figuring out what they wanted to say with the marketing in the first place. And then there are the reports that there were earlier and potentially more robust marketing plans that were inexplicably scrapped. In any case, signs indicate that a variety of issues were in play.

My takeaway about the campaign overall was that Disney was trying to sell the movie as though it were an original, not an adaptation, and even then there was no focus on Andrew Stanton’s record with originals. It’s a head-scratcher that the history of the property wasn’t emphasized even after the “derivative” narrative took root. “Prince of Persia”, “Cowboys and Aliens”, “Attack of the Clones” and “Avatar” were mentioned much too often as having preceded and influenced John Carter. That mistaken public perception could have been addressed early on by a heritage focus. Was the poisonous “derivative” narrative not taken seriously by Disney marketing, or were there simply too few people on the marketing team to turn back the tide?

Perhaps it is easier in retrospect to conclude that it would have been better to inform people about the books and their influence and at least have the chance of more viewers keeping things in perspective. Audiences are used to hearing about source material – it’s not a “dusty old” distraction or fanbase pandering, and it’s not an overestimation of the intelligence of the audience – it’s a familiar and effective selling point. Leaving it out simply neglects to offer something that WILL hook some of the potential audience. I have read many comments across the internet from people who found out about the source material only after the film was released, and even those who haven’t read any of the books have expressed incredulity at Disney’s lack of meaningful references to Burroughs and his works. Adding ERB’s name to the text at the end of a trailer isn’t enough.

Audiences “know” ERB from the influence he has had on popular culture, but they still need to be intentionally re-introduced to him and his first-hand works far in advance of a theatrical release in order for a project like John Carter to be understood and appreciated in context.

I just wish we cud c a sequel in my lifetime. Will we? I really love this movie and I’m reading the books now. So far I’ve read the first three and Thuvia. I really liked Thuvia — I want to see more of Barsoom on screen. Thnx for trying to help make it happen.

Excellent analysis! I know you don’t come right out and say it — but Disney was clearly asleep at the switch, at a minimum, if not worse. I would love to hear their explanations, but of course they will never give them.